Written by Chloe Hayler

Who are the UCU and what are they striking about?

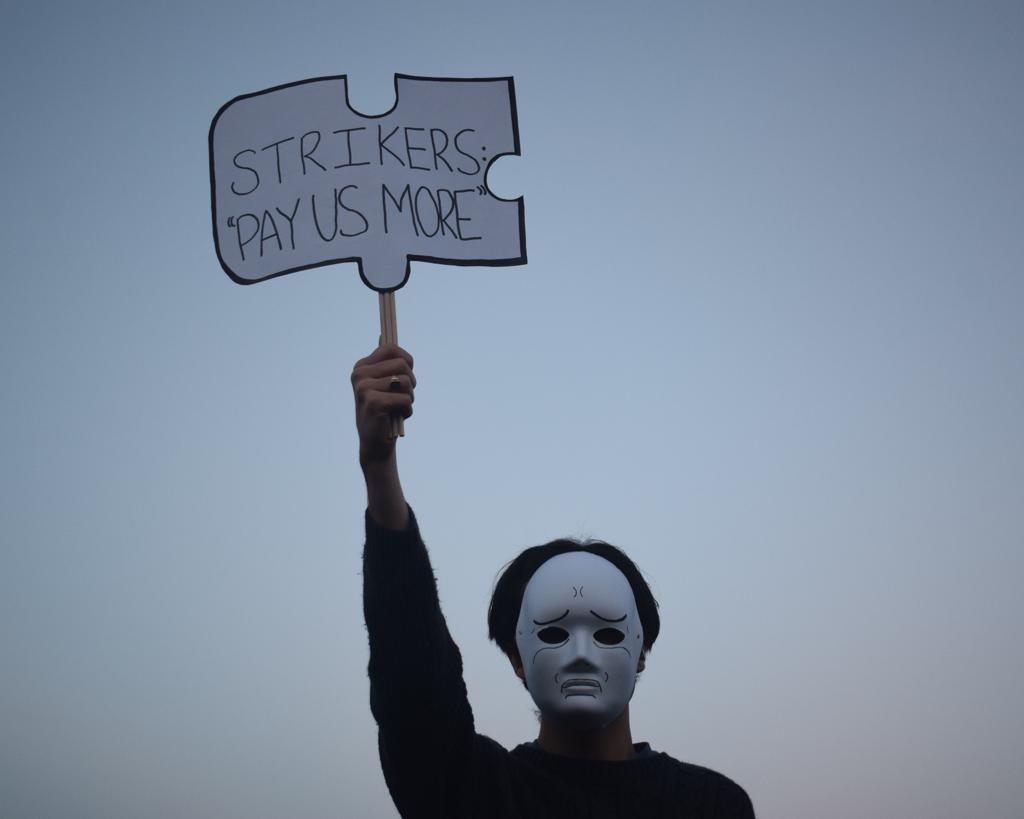

The last academic year has seen the relentless effort of the University and College Union (UCU) in their dispute against the unfair pay and working conditions in institutions across the country.

The UCU is a British trade union representing mainly higher education staff. In this trade dispute with higher education employers, concerning the year 2023/24, the demands are as follows:

- a pay uplift of RPI + 2% or £4,000, whichever is greater, on all pay points.

- nationally agreed action, using an intersectional approach, to eliminate the gender, ethnic and disability pay gaps.

- agreed framework to eliminate precarious employment practices and casualised contracts, including zero-hours contracts, by universities.

- nationally agreed action to address excessive workloads and unpaid work, including addressing the impact that excessive workloads are having on workforce stress and ill-health.

- for the standard weekly, full-time contract of employment to be 35 hours, with no loss of pay.

Has any progress been made in the last year?

Since industrial action first began in November 2022, the Universities and Colleges Employers Association (UCEA) have attempted to make progress, but this has not gone far enough. The UCEA made a tiered offer for 2023/24 pay which was an uplift of 4-5% with some lower salaried roles receiving more. They then offered that part of the uplift would be brought forward to be paid in February 2023, and the rest from August 2023. Representatives of the Higher Education Committee (HEC) rejected this offer, insisting it was not in line with inflation and the lack of provisions for the year 2022/23 was neglectful considering the difficult financial climate.

In March 2023, the HEC voted to put UCEA’s proposals for improved pay, casualisation, workload and equality pay gaps to members via a formal electronic consultative ballot, but recommended rejecting these proposals that were still a pay cut in real terms. In April 2023, UCU members took part, voting to reject. This rejection of UCEA’s proposals led to the start of the marking and assessment boycott from April to September 2023 and during this, UCEA did not make any further offers on pay for 2022/23 or 2023/24.

What actions are strikers taking to put an end to their struggles?

Higher education pay has declined by 30% in real terms since 2009. Surveys conducted by various unions have found that these pay declines have caused staff to fall into an unbreakable cycle of financial struggle. The UCU has revealed that many of its members have had to turn to food banks to feed themselves and their families because employers are simply not paying enough in line with inflation. The cost-of-living crisis has exacerbated this problem…

The use of casual contracts has eroded the rights, protections, and security that should be afforded to all employees and as such, casualisation has caused serious problems for staff. UCU’s research showed that 42% of staff on casual contracts struggled to pay household bills, while many others struggled to make long-term financial commitments like buying a house. A 2019 survey of 3,802 casualised staff in higher education found that 71% of the respondents said their mental health had been damaged by working on insecure contracts and 43% said it had impacted their physical well-being. Casualisation also makes it more difficult for staff to challenge employers about workplace issues, as staff are often reluctant to complain and risk termination of their employment. According to a February 2022 report from the Joint Committee of Experts of UNESCO and the International Labour Organisation, the increase in casualised contracts in higher education has damaged academic freedom. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, employers have chosen not to renew casualised contracts which has made thousands of staff redundant.

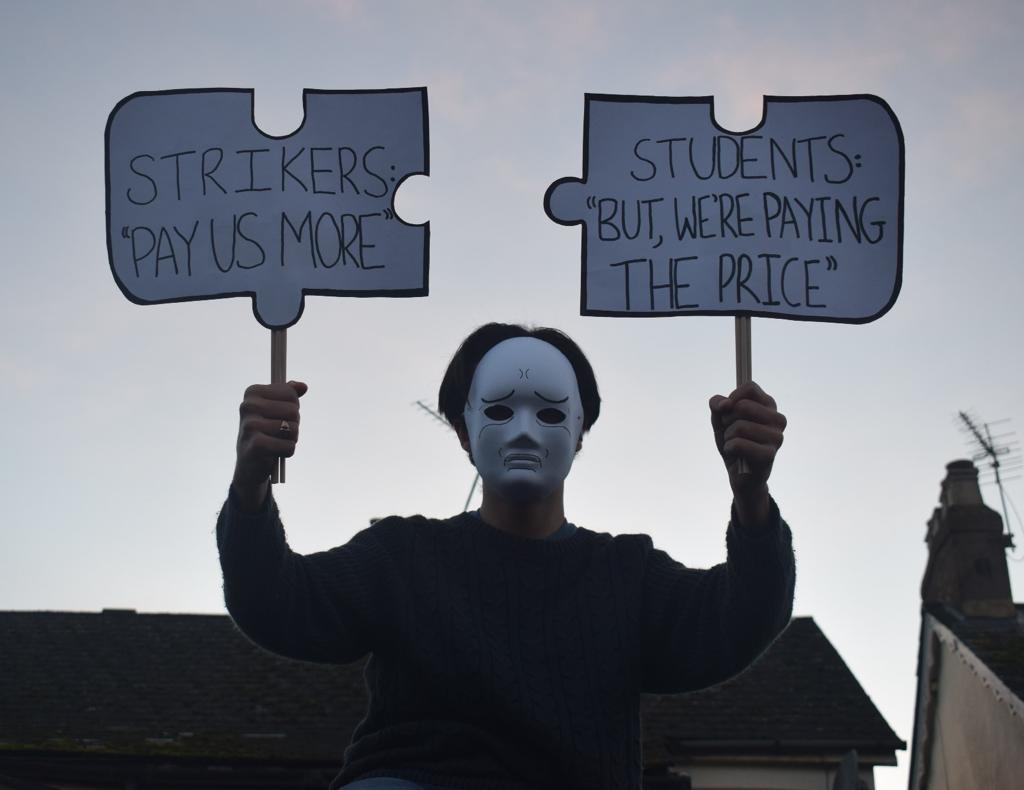

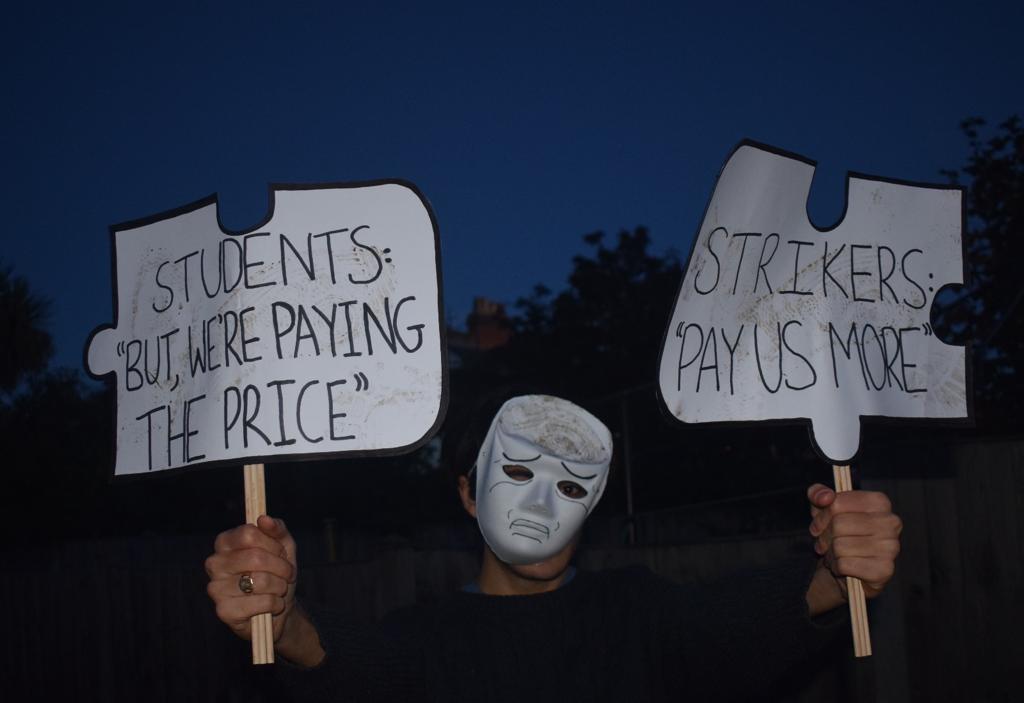

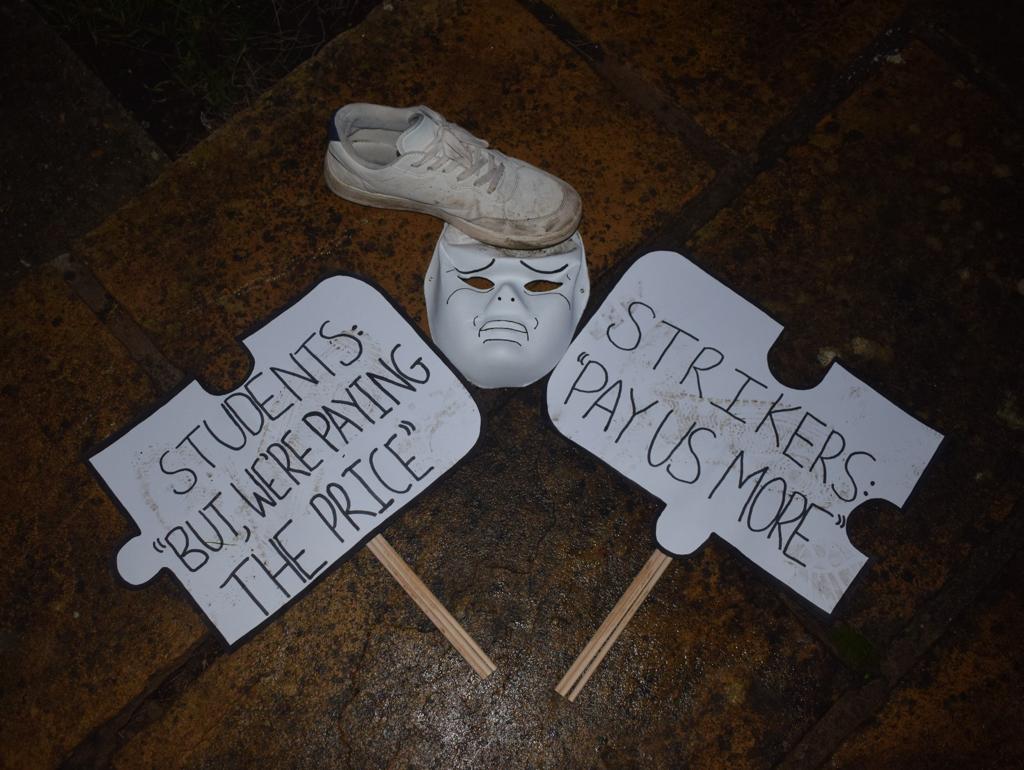

In a bid to eradicate these injustices, the industrial action has included cancellations of lectures and seminars and a marking boycott during exam season. This meant that lessons were simply not held, and any assessments handed in after April 2023 were not marked by professionals. Whilst the marking boycott has since ended, the action continued into the new year with a 5-day strike from the 25th to the 29th of September, causing further disruption to learning. This meant that within a week of beginning the new term, strikers had resumed their fight for a deal. Members of the union are continuing to carry out actions, such as only working to contract hours, not taking on voluntary activities, withholding materials for classes cancelled due to the strikes, not covering for absent staff, and not rescheduling any lectures or seminars that have been impacted.

College staff have also been hit hard by the lack of progress in reaching a deal they feel is fair. College employees across the country are set to continue, with three consecutive days of strike action in place, starting on the 14th of November. In the survey conducted by the UCU, they found that 96% of college staff are “financially struggling because of low wages”, and 79% say this has impacted their mental health.

The UCU insists that the measures they are taking are crucial and necessary to bring about a change in the system. The voices of those on the picket line have not been heard for over 5 years; they are determined to do what it takes to feel valued in their workplaces and to put an end to the money worries of their members.

What impact has the strike action had on students?

There has been widespread support for the action amongst students, with students at some universities chanting “pay your workers” during their graduation ceremony. The National Union of Students has responded with a statement saying: “Staff teaching conditions are students’ learning conditions, and we must fight together for a fairer, healthier education system for everyone who works and studies. Universities and employers must come to the table and take meaningful action to end these disputes. They have a responsibility to their staff and students to end unacceptable pay disparities. As the workers of the future, students have everything to gain from UCU members winning this fight.”

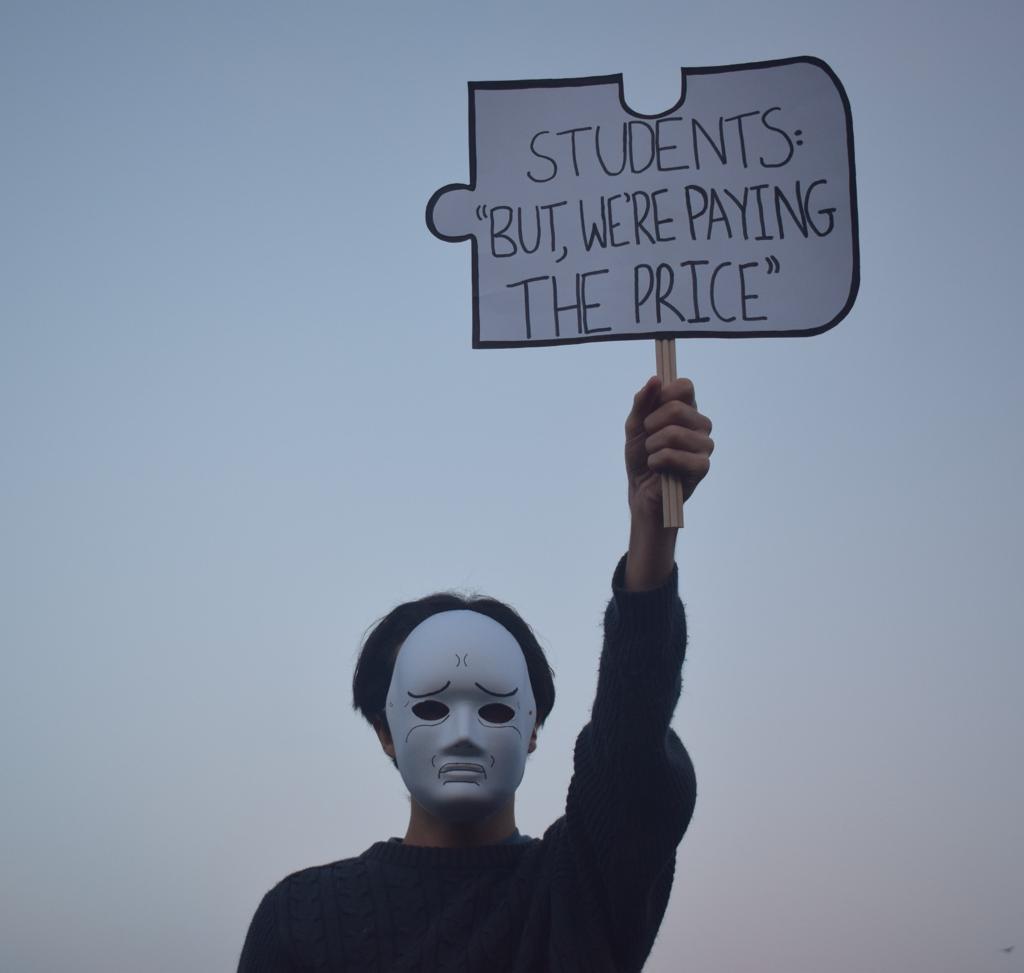

However, it is fair to say that the negative impacts of such extensive strike action have been felt the most by students and they’ve had enough. The marking boycott meant that students were left without definitive grades at the end of the academic year. Several months later, students are still waiting for these marks to be released.

The affected university departments attempted to combat the issue by using systems such as scaling so that students finished the academic year with an estimated grade to their name. However, as a generation of students who endured the process of estimating grades at GCSE and A-Level due to the pandemic, the marking boycott has exacerbated feelings of instability. Uncertainty persists in individuals about how well they are doing in their studies four years on from the beginning of the pandemic.

Another method has been returning exam papers to students after the summer deadlines, allowing them to progress to the next year of their courses regardless of not knowing their grades. However without a firm knowledge of how the previous year went, students feel the hardship of adjusting to levelled content and increased workloads as they progress in their education. Meanwhile, those who graduated are left with pending certificates. With graduate schemes and jobs being competitive to get on to, having unconfirmed degrees is making that process much harder.

Students have also been feeling financial hardship during the strike action. Many universities have seen student groups put up posters demanding refunds for missed lectures, as they question why they are paying full tuition fees if their contact hours are unfulfilled, and papers unmarked.

UCU has openly said, “Members do not relish taking industrial action that affects our students, to whom you have dedicated so much of your energy, even during extremely challenging conditions like the Covid-19 pandemic and national lockdown.” Their action, albeit disruptive, is investing in the quality of education for students and future generations of academic staff.

Thus, much of the anger felt by students has been directed at employers, who fail to put an end to the inequalities faced by higher education staff, causing another year of turbulent learning post Covid-19.

Is there a solution for strikers and students?

According to UCU’s analysis of publicly available data from the financial year 2021/22, universities “generated a record total income of £44.6bn, achieved a total surplus of £2.6bn, ended the year 2021/22 with £19.6bn in cash and short-term investments.” The portion of universities’ money going to its staff hit a low of 51% in 2021. Therefore, the UCU believe employers are wrong to claim that there is no money in the budget to increase pay, transfer staff to permanent contracts, or promote and give secure contracts that reduce unequal pay gaps.

It has been made clear that the industrial dispute will not be concluded without democratic consultation of the UCU members involved. With more strike action planned for the next month, it seems members are not backing down until employers compromise on a sufficient proposal. Students are still left uncertain of how their previous academic year went and should anticipate further disruption to their studies in the year ahead.

The cost of fighting for fairness is clear: several parties are afflicted by the undetermined future, as negotiations ensue between strikers and their employers.

Written by Chloe Hayler, Edited by Eleanor Partington and Paige Tamasi, Photography by Chloe Hayler, Published by Paige Tamasi.